IPO is an organization of international accompaniment and communication working in solidarity with organizations that practice nonviolent resistance.

Where we work:

Artículos relacionados

24.10.11: More Mass Arrests in La Uribe, Meta

30.09.11: MOVICE Leader Carmelo Agámes Freed

3.06.10: Promotion and defense of human rights in the Rural workers reserve zone in the Cimitarra Valley

12.03.10: Second Ecological Camp: Between fear and hope

23.02.09: Peasant-farmers in the Magdalena Medio march to demand their rights

30.07.08: Thefts and Threats Against Cahucopana

21.06.08: Yes, Guamocó exists

19.06.08: Troops from the Special Energy and Highways Battalion #8 breaking International Humanitarian Law

22.01.08: Two More ACVC Leaders Jailed

otros...

15.04.12: Gallery of Remembrance Assaulted, Censored, and Threatened on April 9 in Villavicencio, Meta

18.02.12: Civilian dwellings in Agualinda bombed by the Army’s 4th Division

19.12.11: More Human Rights Violations in Huila

26.11.11: ASOCBAC Leader Fredy Jimenez Assassinated in Taraza

12.11.11: Member of CPDH held captive for 40 days

Topic Tree:

Ambiente

Alternative Comunication

Economia

Sindicatos

Comunidades indígenas

Coca

Comunidades campesinas

International Politic

Politica nacional

Justicia

Kidnapping

Parapolitica

Narcotrafico

Acuerdo Humanitario

Impunity

Ley de Justicia y Paz

Multinacionales y recursos naturales

Politica nacional

Acuerdo Humanitario

Narcotrafico

Parapolitica

Kidnapping

Armed Conflict

Paramilitarismo

FARC-EP

ELN

Plan Colombia

Vioations Human Rights

Positive Faults

Desplazamiento

Asesinados Políticos

Torture

Political Prisoners

Regions

Chocó

Tolima

Catatumbo

Meta

Periferias

Arauca

Magdalena Medio

Nord Est Antioquia

Sur de Bolivar

License

This work is licensed under

Creative Commons

PayPal

Interview with Miguel Ángel González Huepa, recently freed political prisoner

28.08.09

by Maria del Mar Mogedas and Eva Lewis

International Peace Observatory

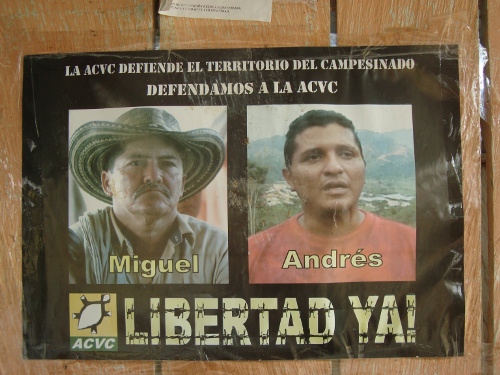

Miguel Ángel González Huepa, recently released in the ACVC office

Miguel Ángel Gonzalez Huepa (MH) is the most recent of six leaders of the Farmers Association of the Cimitarra River Valley (ACVC) to be freed after spending 17 months in prison accused of rebellion. The ACVC community organizer Andrés Elías Gil is still in prison and there are various arrest warrants still pending against other members of the association. Miguel was arrested on January 19th 2008, and he spent the next 17 months, without ever being found guilty, in the La Modelo Prison of Bucaramanga and the maximum security prison Palo Gordo. A week after his arrest his son Miguel Ángel Gonzalez Gutierrez was assassinated and presented as a guerrilla killed in combat, (known as a false positive) by members of the Calibío Battalion of Colombia’s national army. Miguel Huepa was released from prison on the June 9th 2009, and several days later in the ACVC’s office in Barrancabermeja he granted an interview to members of the International Peace Observatory (IPO).

IPO: Can you explain the legal process against you starting from the time of your arrest?

MH: Yes, this is something that has to do with all the work of the Association. It is not so much a persecution of the individual person as of the organizational process and the name of the ACVC. First they captured Óscar, Andrés and Mario, then came the comment that the rest of us leaders that work with the ACVC had warrants pending for our arrest. Well, I never received in my hands a document saying there is an order for your arrest. In the countryside, in the village Puerto Nuevo Ité in January we organized a meeting for the 19th of January 2008. The sergeant Chaverrio was present in the meeting, we called him to ask him why they were arresting people they were saying were guerrillas when they weren’t. He said that under his watch no more of these types of cases were going to occur, cases of false operations like assassinations. Well, that was the big lie that he told the community, because it wasn’t like that. In the afternoon the army was surrounding the people. When I got up a corporal said to me “Who do you want to be the witness for your arrest?” I said to him, “Well, here is my son, his name is Miguel Ángel also, Miguel Ángel Gonzalez Gutierrez.” Then he told me “You are under arrest.” He asked if is I had been trying to flee, I was never fleeing because I haven’t done anything wrong. [The next day] we arrived in Caldas at around 10:00 at night, well, the people, the leaders and other activists were all completely uninformed. We slept in a cell and I was put in handcuffs for the first time. I felt very bad, and they took me to the offices of the DAS (Administrative Department of Security) in Bucaramanga, until the 24th of that month. Then I arrived at La Modelo where my other comrades were being held, I arrived with Ramiro, who had also been captured in the same village, and from there the process continued. Three comrades were freed, that was Mario, Evaristo and Oscar. Some time later Ramiro was freed. The process went on, it was me with Andres. We began to go to Barranca for the public hearings and move forward with the process month by month.

Poster demanding freedom for Miguel Huepa y Andrés Gil, in a village in the Nordeste Antioqueño

IPO: How did it happen that were you freed?

MH: What the witnesses said really didn’t match up at all, there was a lot of contradictions, one would say one thing, and another would say something else, one would say one date and another would say another. There was no justification for our arrests, because many of the things were false and what could be seen was that it was a set up. So what one comes to understand is that since they didn’t find proof they had to free us, because they couldn’t hold us any longer.

IPO: How are the conditions in the prisons?

MH: It is hard in the prison yards, in this case I would be talking about Yard 8 in Palo Gordo, life is hard because there are the AUC (paramilitaries), the ELN guerrillas and the FARC, those who belong to different community organizations, like us, and common criminals. That’s what makes life bad in prison. [On the other hand, La Modelo] isn’t maximum security, there are more options, many more possibilities, every week there are visits…. all day. Meanwhile in Palo Gordo they only give you three hours every two weeks and a conjugal visit once a month. In the Modelo Prison in Bucaramanga there are all around more advantages, bringing in food, they let in more clothes, televisions, bigger radios, whereas in Palo Gordo there they only let you have radios with small batteries.

IPO: How was the treatment you received from the prison authorities?

MH: Well, I don’t complain, because my behavior couldn’t have resulted in anything other than them respecting me. Discipline makes them respect you. No one hit me, no one insulted me even, what things there were, were general, words… a commander would come and say “Fuckers, you all have to adapt to things here, you will adapt or you will adapt, or I will lock you up for two weeks, but here I am the one in charge! Here you are under the authority of INPEC (the prison authorities)” That is for everyone, but as an individual person everything was fine…. [Until] there was a commotion with the guards, they gassed us and beat some people. Then we went to Palo Gordo, to suffer the consequences of the gas, because then we had to mix with AUC, with common criminals, with all different kinds of people who had committed different crimes, and these people fought a lot and they gassed us a lot.

IPO: What was the organization of political prisoners like inside the prisons?

MH: Yard 4 in Bucaramanga is a political prisoners yard, which has been defended tooth and nail with documentation and countless other things. It is a right, a constitutional right and guaranteed by the internal prison regulations. There the political prisoners consist of guerrilla prisoners. FARC, ELN are the two biggest groups, people also talked about the EPL. They lump us all together as ‘political’. In the political yard everyone lives with clear policies about human behavior, applying human rights and respect for everyone’s ideas. There are people who because they like the behavior of the people in that yard, would ask to go there, and they would be received. They were mostly common criminals, but they also had to adapt to the rules of the yard, the discipline more than anything. If some young guy creates a disturbance in the yard there is a leadership. That is what is different about the political yard, that there is a leadership made up of different groups and they form a committee that manages the patio. There they don’t allow drugs. That’s why there aren’t problems. So one lives well in the sense that there wasn’t tear gas.

IPO: What kind of solidarity did you feel from people on the outside?

MH: There were people in Bucaramanga from the political prisoners committee, a lawyer’s organization, a group of students from the UIS and some community organizations. In Barranca we can say that there was a lot of solidarity in one way or another from the majority of organizations and from the farmers. This helped a lot, the presence of farmers in the public hearings, they brought children as well, and community leaders like presidents of the community councils, human rights representatives and general community members. So one feels very good in that sense because the people have always remembered me and they never abandoned me when I was in prison.

IPO: Do you believe that you were freed due to the efforts of the ACVC?

MH: Yes, of coarse. For one because the evidence didn’t match up and the other because of the peoples’ works, the people’s pressure speaks for itself. If these men were bad or they did something, well why do the people like them? So this has been very helpful and it will continue to help in the defense of comrades, and when other comrades fall we’ll have to follow the same process, and the people will do it more and more.

IPO: What hopes are there for the freedom of your colleague Andres?

MH: The hope is this: to continue with the fight, with the demands to the state and to look at things clearly and conclusively about human rights violations. It is not what one person says, or what the other says, but the fact that there isn’t clear evidence. If there isn’t evidence they have to do the same thing that they have done with all the rest of our comrades because there should be equal rights. So the hope is great that he is headed for freedom.

IPO: What political work are you planning on realizing in the coming days?

MH: At the moment we haven’t yet done the evaluation of the work groups and [I need to think about my] personal security. I have to think about what I am going to do but the will is there. We continue to carry out the political work on the farmers’ economic situation, with projects that some national and international entities are supporting us with. In Colombia it is not a question of pleading because we are not beggars, but rather it is the obligation, the constitutional duty to help the people cover their basic needs. From the international organizations we need support and from there we’ll just keep knocking on doors.

IPO: Are you going to denounce your son’s assassination before the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Puerto Berrío?

MH: I’m not sure, we are looking into that now, taking slow steps towards going to Puerto Berrío if there is a need. For many reasons it needs to be looked at carefully because the wife of my murdered son is going, she has been the one who has really been on top of the whole process. There is a press conference, so that is where I am going to tell all the things that have been happening so that the world will know.